Readings in Contemporary Poetry

Alice Notley and Brenda Coultas

Thursday, November 10, 2011, 6:30 pm, Dia Chelsea

Thursday, November 10, 2011, 6:30 pm

535 West 22nd Street, 5th Floor

New York City

Introduction by Vincent Katz

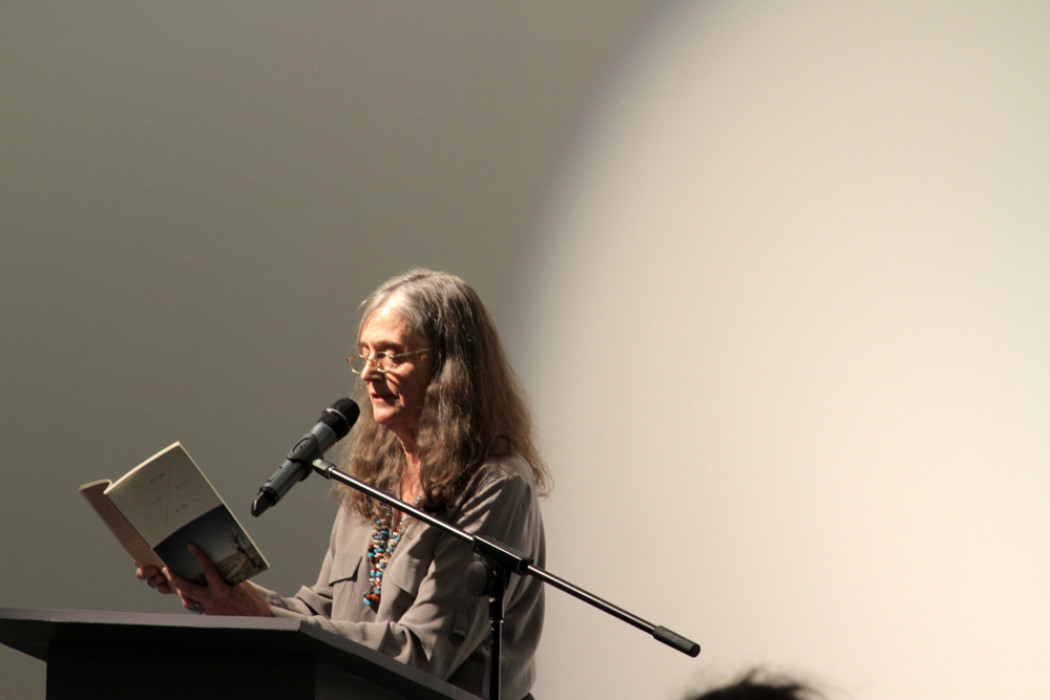

Alice Notley

Alice Notley has published over thirty books of poetry, including Culture of One, Reason and Other Women (2010) and Grave of Light, New and Selected Poems 1970-2005 (2006). With her sons, Anselm and Edmund Berrigan, Notley edited The Selected Poems of Ted Berrigan (2011) as well as The Collected Poems of Ted Berrigan (2005). She is also the author of a book of essays on poets and poetry, Coming After (2005). Notley is the recipient of numerous awards and prizes including the Academy of American Poets’ Lenore Marshall Prize and the Poetry Society of America’s Shelley Award.

CITY OF GHOSTLY FESTIVALS

Try to find

the center of night. this city

A hear break, I can’thearit.

Dido the appropriatedvictim

sets all the bottlesrattling

in the wind of ouragains.

I wanted a differentagain.

It’sdifferent.

_______________

The syllabary

ofmy

sins

a

thingMaat

flicks

into

the river

running

judgment

a million literalyears of.

I’msick of judgingyour carnage,

shesays,

you are all leftalone

withit.

_______________

Dido’s job

fortwothousandyears

has been to

commit suicide

after

herdeath, and after

the Romans destroy her

foundation.

_______________

The witch’s job. is to change

time

whichruns in short lines

between

eventslikeinnumerable

falls of cities

iswatching me. But itisn’t.

If you change the nature of

events

doyou change time?

Event: Isat down to

talk to everyone

whohadeverlived.

_______________

‘My country

isbroken and itcan’tbefixed’

timelovedso

femina-hating Rome

alwaysfalling

I, the witch, pardon no one

instead, I change Dido’s job.

_______________

Man withwhomeverythingis

boring

everythinghedoes and that one

doeswithhim

isboring. One iscondemned

tobe part of his

boring world.

There isanother man

withwhomone’scondemned

tobe

duplicitous

Everything’s a cheat a scam

in the big-guy road-house world

Help him tell lies. wearspecial

clothes

forthat.

_______________

THIS WAS HOW I BROKE IT

Theytold me I couldn’t have

it -- time -- so

I tookit.

I put him away

whohadwithered to a doll.

_______________

Weghoulswaitingoutside of time . . .

Dido to poem: Do all myremembering

now

so city continues.

Do weacceptitsaysvoice

He becametooold to bewise; we

had to stepoutsidehim

andintoknowledge

ofpoetry, the ghoulish, timeless state.

_______________

This poem, the poem,

always

my real country

the center of night. this city

A hear break, I can’thearit.

Dido the appropriatedvictim

sets all the bottlesrattling

in the wind of ouragains.

I wanted a differentagain.

It’sdifferent.

_______________

The syllabary

ofmy

sins

a

thingMaat

flicks

into

the river

running

judgment

a million literalyears of.

I’msick of judgingyour carnage,

shesays,

you are all leftalone

withit.

_______________

Dido’s job

fortwothousandyears

has been to

commit suicide

after

herdeath, and after

the Romans destroy her

foundation.

_______________

The witch’s job. is to change

time

whichruns in short lines

between

eventslikeinnumerable

falls of cities

iswatching me. But itisn’t.

If you change the nature of

events

doyou change time?

Event: Isat down to

talk to everyone

whohadeverlived.

_______________

‘My country

isbroken and itcan’tbefixed’

timelovedso

femina-hating Rome

alwaysfalling

I, the witch, pardon no one

instead, I change Dido’s job.

_______________

Man withwhomeverythingis

boring

everythinghedoes and that one

doeswithhim

isboring. One iscondemned

tobe part of his

boring world.

There isanother man

withwhomone’scondemned

tobe

duplicitous

Everything’s a cheat a scam

in the big-guy road-house world

Help him tell lies. wearspecial

clothes

forthat.

_______________

THIS WAS HOW I BROKE IT

Theytold me I couldn’t have

it -- time -- so

I tookit.

I put him away

whohadwithered to a doll.

_______________

Weghoulswaitingoutside of time . . .

Dido to poem: Do all myremembering

now

so city continues.

Do weacceptitsaysvoice

He becametooold to bewise; we

had to stepoutsidehim

andintoknowledge

ofpoetry, the ghoulish, timeless state.

_______________

This poem, the poem,

always

my real country

Brenda Coultas

Brenda Coultas’s publications include The Marvelous Bones of Time (2007), A Handmade Museum (2003), which won the Norma Farber First Book Award from The Poetry Society of America and a Greenwald grant from the Academy of American Poets, and Early Films (1996). She was a Distinguished Visiting Writer at Long Island University in 2009 and a New York Foundation for the Arts Fellow in 2005. Her poetry has been published in The Brooklyn Rail, Witness, Volt, and other journals.

_____from The Tatters

The feather this afternoon is a black and grey tongue pointing east. The pay phone, a portal through which voices connect in sometimes pleasing ways. The hood of the half booth as private as a homemade sex tape.

I, the relic on the street, born during the time of paper and print. My replacements, attached to wireless networks, ride herd down the sidewalk.

Holding close, slowing down to read the sign in the booth, tear off a tab of “I will post your flyers.”

University bus drives by: sadness ensues.

My days are spooked by the rotary ringtone of a cell phone ghosting a black enamel phone, heavy, and tethered to earth: that is a desk, that is gravity.

To open the folding door of the booth is to enter into a cabinet of curiosities: a carnival wagon. The rotary dial is a greased wheel of chance.

In airport corridors clusters of laptops and pay phones await flight. A stranger no longer taps on the glass.

Feathers are bits of bird. Eggs, an afterthought for this observer.

Once the neighbors played a recording of falling coins or stuck a pin into the receiver for free calls. This was in the past, although that is clear, I say it for myself before the time caught in the mirror turns amber.

Entering the carny wagon of childhood games: nickel pitch, shooting gallery, balloon burst, cranes/diggers, weight and age barkers. I prize gun-shaped cigarette lighters, girlie cards, switchblade combs, and stuffed bears. I do not prize plastic poodles. Now, I prize grainy vintage porn and airbrushed nudie calendars, or return to the flea market to gaze at a portrait of a bored couple in the 1920s posing with a headstone or a Chinese tea box full of loose sequins in rotting paper or a Buddha head a Vietnam vet souvenir or shreds of Nepali armor, or a Weimar Republic glossy of nightclub performers or journal, in English and Arabic. Translations of homilies. I bid on these tatters.

Separated coffee and milk at peace inside the cup on the street. Hard core cooing, brooding, in the back of the railroad apartment. A pillow propped against the boutique door. White wing spreads out from back of the locust tree.

Cup in the booth, finger streaks of Irish Rose on the walls.

Tintype of man with hand on his heart. My other hand is on the daguerreotypes. My eyes on a cloth monkey dressed in a suit and tie. My toes in my shoes and my hands at the ends of my arms.

The cup on top of the time machine makes a composition; What is a receiver? A cradle? What is “return?” The coin slot is a finger dip in into the dark.

Where are the cool blue mint hoods of Brazil?

“Mary had a little lamb,” were the first words.

The silver of the daguerreotype serves as my mirror. I’m building a time machine made from parts of the past, for when I might return through an old memory stored in wood.

I, the relic on the street, born during the time of paper and print. My replacements, attached to wireless networks, ride herd down the sidewalk.

Holding close, slowing down to read the sign in the booth, tear off a tab of “I will post your flyers.”

University bus drives by: sadness ensues.

My days are spooked by the rotary ringtone of a cell phone ghosting a black enamel phone, heavy, and tethered to earth: that is a desk, that is gravity.

To open the folding door of the booth is to enter into a cabinet of curiosities: a carnival wagon. The rotary dial is a greased wheel of chance.

In airport corridors clusters of laptops and pay phones await flight. A stranger no longer taps on the glass.

Feathers are bits of bird. Eggs, an afterthought for this observer.

Once the neighbors played a recording of falling coins or stuck a pin into the receiver for free calls. This was in the past, although that is clear, I say it for myself before the time caught in the mirror turns amber.

Entering the carny wagon of childhood games: nickel pitch, shooting gallery, balloon burst, cranes/diggers, weight and age barkers. I prize gun-shaped cigarette lighters, girlie cards, switchblade combs, and stuffed bears. I do not prize plastic poodles. Now, I prize grainy vintage porn and airbrushed nudie calendars, or return to the flea market to gaze at a portrait of a bored couple in the 1920s posing with a headstone or a Chinese tea box full of loose sequins in rotting paper or a Buddha head a Vietnam vet souvenir or shreds of Nepali armor, or a Weimar Republic glossy of nightclub performers or journal, in English and Arabic. Translations of homilies. I bid on these tatters.

Separated coffee and milk at peace inside the cup on the street. Hard core cooing, brooding, in the back of the railroad apartment. A pillow propped against the boutique door. White wing spreads out from back of the locust tree.

Cup in the booth, finger streaks of Irish Rose on the walls.

Tintype of man with hand on his heart. My other hand is on the daguerreotypes. My eyes on a cloth monkey dressed in a suit and tie. My toes in my shoes and my hands at the ends of my arms.

The cup on top of the time machine makes a composition; What is a receiver? A cradle? What is “return?” The coin slot is a finger dip in into the dark.

Where are the cool blue mint hoods of Brazil?

“Mary had a little lamb,” were the first words.

The silver of the daguerreotype serves as my mirror. I’m building a time machine made from parts of the past, for when I might return through an old memory stored in wood.

Explore

Alice Notley Audio from Readings in Contemporary Poetry

Move to Alice Notley Audio from Readings in Contemporary Poetry pageBrenda Coultas Audio, Readings in Contemporary Poetry

Move to Brenda Coultas Audio, Readings in Contemporary Poetry page