Louise Bourgeois

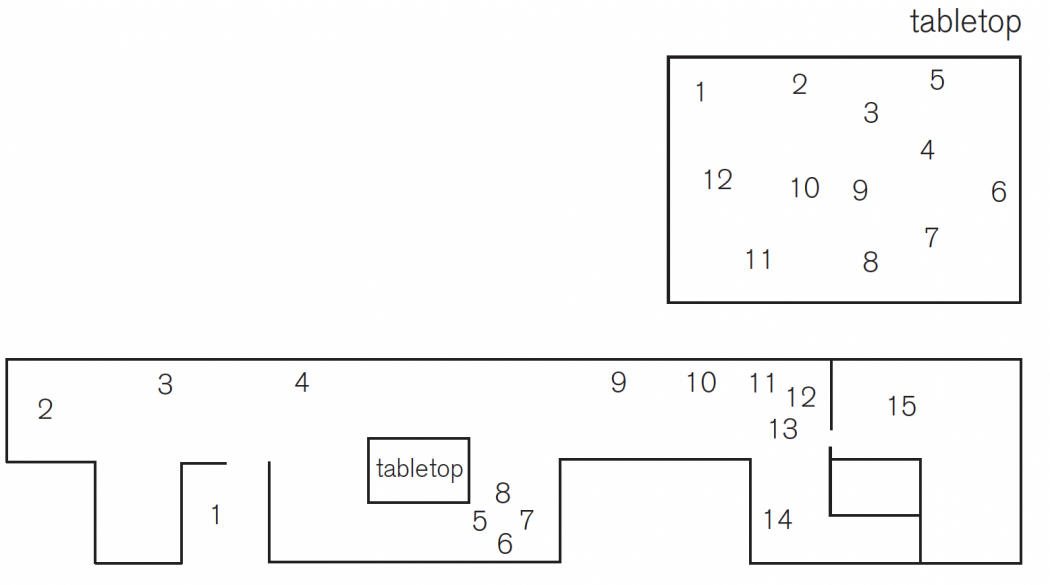

Long-term view, Dia Beacon

Overview

“Every day,” Louise Bourgeois said, “you have to abandon your past or accept it, and then, if you cannot accept it, you become a sculptor.” For her, making art entails trying to translate experience into form—an operation that she compares with exorcism. In Bourgeois’s works on view in these galleries, organic formations fuse with the inorganic materiality of the media in which they are rendered, be it marble, wood, or bronze. The artist’s repertoire of materials spans traditional media and new textures, such as latex and synthetic resin. In her work, representation often entails the creation of a surrogate for the body and its suffering organs.

Mnemonic, symbolic, evocative, and restrained—these strong, if contradictory, qualities are typical of Louise Bourgeois’s sculpture. “Every day,” she declared, “you have to abandon your past or accept it, and then, if you cannot accept it, you become a sculptor.” For her, the art-making process was a search for the forms that translate experiences—an operation that she compared with exorcism. The sculptor is her own healer, the work a sort of proxy that reveals the forms of trauma: elusive, almost abstract, but also descriptive. In Bourgeois’s figures, one can recognize limbs, organs, and organic formations that fuse with the inorganic materiality of the medium, be it marble, resin, wood, or bronze. In fact, the choice of a specific material was something completely intuitive for the artist: “The medium is always a matter of makeshift solutions. That is, you try everything, you use every material around, and usually they repulse you. Finally, you get one that will work for you. And it is usually the softer ones—lead, plaster, malleable things. That is to say that you start with the harder thing and life teaches you that you had better buckle down, be contented with softer things, softer ways.”

As illustrated in this presentation in Dia:Beacon’s attic—a place akin to the intimate mood of Bourgeois’s art—the artist’s repertoire of materials was as connected to traditional media such as bronze or marble as it was open to new textures, such as those of latex and synthetic resin. Latex, in its similarity to human skin, conveys a feeling intrinsic to Bourgeois’s aesthetic, where representation often entails the creation of a surrogate for the body and its suffering organs. Yet her images of the body point not at its appearance, but the way it is perceived from within. Bourgeois’s body is a psychological, internalized one—the body as it is experienced by the sufferer—and the accumulations of members and membranes are symbolically powerful because they are imaginary.

Interconnections among different moments in time infuse Bourgeois’s approach to art making as well as the objects she generates: over a career of more than seventy years, she repeatedly returned to particular motifs, constantly probing, expanding, and reformulating their forms. Certain works suggest an intricate relationship between architecture—the living space where feelings are transferred— and the human body—understood as the (haunted) house of the self. “Space does not exist,” Bourgeois claimed. “It is just a metaphor for the structure of our existence.” This idea is already present in her first mature works, made in the 1940s, when she began to explore a concept she called the femme-maison, or “woman-house.” In the 1960s, this concept bifurcated into various related series—Soft Landscapes, Lairs—expressive of both haven and prison, refuge and trap.

Some sculptures evoke human shelters and those made by other creatures—cocoons, carapaces, shell-like vessels—at the same time that they are rife with allusions to the body. In later series, notably exemplified here by Crouching Spider (2003), the organic aspect is emphasized, and the predominant feeling is exacerbated: cold, threatening, and unforgiving. A frequent subject in her later work, the spider is a weaver. Tellingly, as a child, Bourgeois worked with woven fabrics, helping her parents in the family business of tapestry repair. This dichotomy between protection and threat expresses Bourgeois’s ambivalent idea of maternity. But, though all her works are resolutely autobiographical, the artist refused to assign rigid meanings to her pieces. They are expressions of desire and trauma, simultaneously physical and invisible, bodily and amorphous.

- Fée couturière, 1963

Painted bronze; edition 6/6

Collection Louise Bourgeois Trust - The Quartered One, 1964–65

Bronze with patina; edition 3/6

Collection The Easton Foundation - Lair, 1962

Plaster

Collection The Easton Foundation - Amoeba, 1963–65

Painted bronze

Collection The Easton Foundation - Hanging Janus with Jacket, 1968

Bronze; edition 1/6

Collection The Easton Foundation - Janus, 1968

Bronze; edition 1/6

Collection The Easton Foundation - Janus in Leather Jacket, 1968

Bronze; edition 2/6

Collection Louise Bourgeois Trust - Inner Ear, 1962

Bronze with nitrate patina; edition 4/6

Collection Louise Bourgeois Trust - Avenza Revisited II, 1968–69

Bronze with nitrate patina; edition 1/6

Collection Louise Bourgeois Trust - Memling Dawn, 1951

Bronze and stainless steel

AP 1/1, edition of 6

Collection The Easton Foundation - Untitled, 1954

Painted cork and stainless steel

Collection The Easton Foundation - Untitled, 1954–62

Painted wood, latex, and stainless steel

Collection The Easton Foundation - Untitled, 1954

Painted wood and stainless steel

Collection The Easton Foundation - Maisons Fragiles, 1978

Steel

Courtesy Cheim & Read and Hauser & Wirth - Crouching Spider, 2003

Bronze, polished patina, and stainless steel;

edition 2/6

Collection Louise Bourgeois Trust

tabletop:

- Labyrinthine Tower, 1962

Bronze; edition 2/6

Collection Louise Bourgeois Trust - The Open Hand (variant), 1966

Bronze; edition 1/2

Collection Louise Bourgeois Trust - End of Softness, 1967

Bronze with patina; edition 3/6

Collection The Easton Foundation - La Patte, 1965

Bronze with nitrate patina; edition 3/6

Collection Louise Bourgeois Trust - The Fingers, 1968

Bronze; AP

Collection The Easton Foundation - Etretat, 1960

Bronze with nitrate patina; edition 1/6

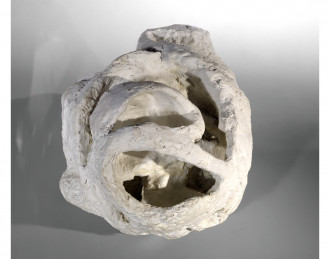

Collection Louise Bourgeois Trust - Lair, 1962

Plaster; exhibition copy

Collection The Easton Foundation - Three Roses, 1968

Bronze; edition 1/6

Collection Louise Bourgeois Trust - Germinal, 1967

Bronze; edition 2/6

Collection The Easton Foundation - The Goodies, 1961

Plaster, wood, wire, and glue

Collection The Easton Foundation - Unconscious Landscape, 1967–68

Bronze with patina; edition 1/6

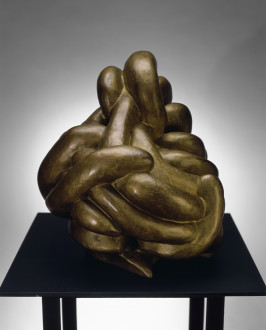

Collection The Easton Foundation - Clutching, 1962

Bronze with patina

AP 1/1, edition of 6

Collection The Easton Foundation

Louise Bourgeois was born in 1911 in Paris. She entered the Sorbonne to study mathematics in 1932 but turned to art the next year. She enrolled at several art schools, including the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, in addition to apprenticing in artists’ studios in Montparnasse and Montmartre. She then immigrated to New York in 1938, and continued her studies at the Art Students League. Her first one-person exhibition was held at the Bertha Schaefer Gallery, New York, in 1945, and her sculpture was first shown in 1949 at the Peridot Gallery, New York. In 1982 the Museum of Modern Art, New York, organized a retrospective, which traveled to various American venues. Her work has since been shown internationally, including in Documenta 9, Kassel, Germany (1992), and the São Paulo Bienal (1996). Bourgeois’s first European retrospective was organized in 1989, traveling from the Frankfurter Kunstverein to the Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich, and the Fundació Antoni Tàpies, Barcelona, among other venues. Bourgeois represented the United States at the Venice Biennale in 1993. Tate Modern, London, organized a major traveling retrospective of her work in 2007. Bourgeois died in New York City in 2010.

Related Events

Dia Talks

Julia Phillips on Louise Bourgeois

Wednesday, May 1, 2024, 6:30 pm, Dia Chelsea

Artist

Louise Bourgeois

Louise Bourgeois was born in Paris in 1911. She died in New York City in 2010.

Selected Works on View

Louise Bourgeois

Hanging Janus with Jacket, 1968

Go to Hanging Janus with Jacket page

Louise Bourgeois

Janus, 1968

Go to Janus page

Louise Bourgeois

Janus in Leather Jacket, 1968

Go to Janus in Leather Jacket page

Louise Bourgeois

Fée couturière, 1963

Go to Fée couturière page

Louise Bourgeois

Labyrinthine Tower, 1962

Go to Labyrinthine Tower page

Louise Bourgeois

Lair, 1962

Go to Lair page

Louise Bourgeois

The Fingers, 1968

Go to The Fingers page

Louise Bourgeois

End of Softness, 1967

Go to End of Softness page

Louise Bourgeois

Germinal, 1967

Go to Germinal page

Louise Bourgeois

Unconscious Landscape, 1967–68

Go to Unconscious Landscape page

Louise Bourgeois

Three Roses, 1968

Go to Three Roses page

Louise Bourgeois

Etretat, 1960

Go to Etretat page

Louise Bourgeois

Lair, 1962

Go to Lair page

Louise Bourgeois

Avenza Revisited II, 1968–69

Go to Avenza Revisited II page

Louise Bourgeois

The Open Hand (variant), 1966

Go to The Open Hand (variant) page

Louise Bourgeois

Clutching, 1962

Go to Clutching page

Louise Bourgeois

The Goodies, 1961

Go to The Goodies page

Louise Bourgeois

Crouching Spider, 2003

Go to Crouching Spider page

Louise Bourgeois

La Patte, 1965

Go to La Patte page

Louise Bourgeois

Memling Dawn, 1951

Go to Memling Dawn page

Louise Bourgeois

Untitled, 1954

Go to Untitled page

Louise Bourgeois

Untitled, 1954 c.

Go to Untitled page

Louise Bourgeois

Untitled, 1954

Go to Untitled page

Louise Bourgeois

The Quartered One, 1964–65

Go to The Quartered One page

Louise Bourgeois

Maisons Fragiles, 1978

Go to Maisons Fragiles page

Louise Bourgeois

Inner Ear, 1962

Go to Inner Ear page

Louise Bourgeois

Amoeba, 1963–65

Go to Amoeba pageExplore

Elaine Reichek on Louise Bourgeois

Move to Elaine Reichek on Louise Bourgeois pagePatty Chang on Louise Bourgeois

Move to Patty Chang on Louise Bourgeois page

Elaine Reichek on Louise Bourgeois

Move to Elaine Reichek on Louise Bourgeois page